Skin Physioanatomy 101

Layers of the Skin

We may think of skin as one big structure, the bit that we can see. In reality, there are many layers that make up the skin, each with different groups of functions.

Here, we outline what these are in a visual way, going from superficial (the skin that we can see) to deep (the layers that we can't see).

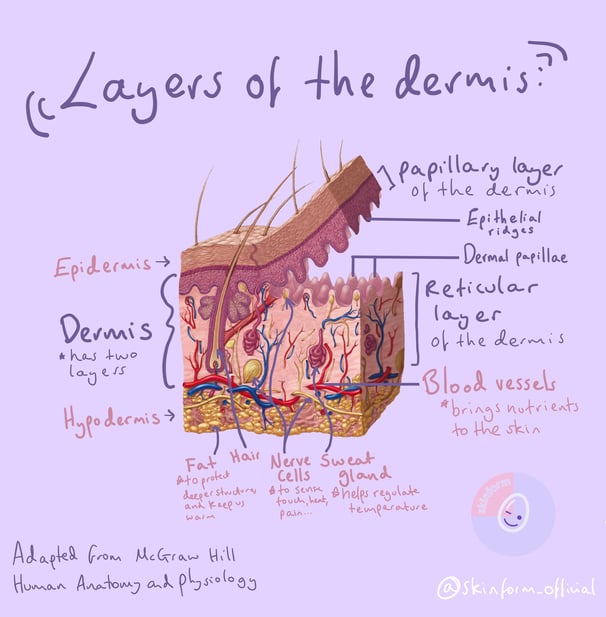

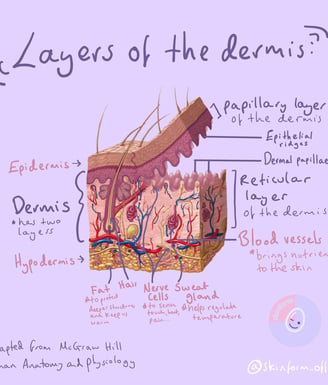

The big picture:

In this image, we can see a cross-section of the skin, from the top (where we see pores and hair exiting the skin) to the deeper bits (where we find fat, muscle, and bone).

The labelled structures are the most fundamental parts to know about. Note things like the oil glands - called sebaceous glands in medical terms - which are involved in over-productive conditions like acne, and under-productive ones like dry skin.

Let's start from the top...

The most superficial layer of the skin is the epidermis.

The epidermal layer of the skin is made up of five layers. From superficial to deep (i.e. top to bottom) these are: the strata corneum, lucidum, granulosum, spinosum, and basale. You can remember these with the mnemonic 'Creating Lovely Glowing Skin, Brilliant'.

The benefits of understanding the layers of the epidermis are multiple. Some are that, first, the epidermis is how the outermost part of the skin interacts with the world around us. By understanding how it does this, we can better appreciate how things like suncare, moisturising, and exfoliation impact the skin.

Second, topical treatments for the skin, including both pharmaceutical products and cosmetic skincare bought in a store, act first on the epidermis. Knowing a bit about this layer hence allows you to be able to understand how your treatment works if it is acting on the top layers of your skin.

Third, some skin conditions originate at the level of the epidermis. Having a basic knowledge of what is found in this area and how it is intended to work means that you can do your own further research from scientific sources about your skin condition, opening up new avenues of education for you.

Epidermis -> 'epi' (upon) + 'derma' (skin). Meaning the top layer of the skin.

Topical -> 'topikos' (local) + -al suffix. Meaning that a treatment is placed 'locally' onto the skin as a cream, gel, emollient, etc.

The tough bit...

The second layer of the skin - which varies in thickness depending on the part of the body - gives the skin its toughness against injury, assists in sensing touch, and allows the deeper structures to function in cooperation with the more superficial ones.

It can be further subcategorised into the papillary layer and the reticular layer.

The papillary layer forms a bobbly surface that faces downwards, reaching towards the inside of the body. This regular pattern of the 'epidermal ridges' makes the surface area of the upper part of the dermis more flexible, meaning that the skin can have a bit of stretch when pulled under tension.

The reticular layer is thick, comprised mostly of tough (but also slightly flexible) collagen fibres. It bobbles upwards, holding hands with the ridges just above. This layer gets thinner as we age, resulting in the softening of the skin into wrinkles.

In the diagram to the right, we see the small red branches of the arteries at the deepest part of the dermis, which bring nutrients and oxygen from the blood to supply the top layers of the skin. The small blue veins go in the opposite direction, taking carbon dioxide and toxins away from the skin to be taken away and processed.

Hair bulbs are also found in the dermis. This is where hair is formed, gradually pushing previously-made hair upwards over time.

Alongside this hair follicle we find sebaceous glands. These produce 'sebum', an oily substance that keeps the skin supple and healthy. In people with particularly oily skin, sebum can build up and clog the pores from which exit the hair shaft. This provides an environment for bacteria to grow, which is one cause of acne.

We can also see parts of nerve cells.

'Nerves' can be incredibly long, as they usually connect all the way from the brain and spinal cord to the tips of the fingers. For nerves to function, they need a receptor (to pick up signals) and small branches connecting the receptors to the deeper nerves (to send the signal off to the brain to interpret). There are lots of different types of receptors. They sense things like light touch, vibration, heat and cold.

This is relevant to things like burns. If a burn goes into the dermis, these tiny nerves may be damaged. If it starts to reach the base of the dermis, it may then destroy the receptors or sever the connection between them and the deeper nervous system. Even once the area has healed, this can be why an area over a scar may feel numb, as the receptors in the skin may no longer be present, or may no longer be in a continuous connection.

Coming soon...

Hypodermis - The Low Glow

Scarring - what does scarring look like up close and how do scars form?

SKINFORM

COPYRIGHT © 2023 THE SKINFORM ORGANISATION - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Learn about...